Who Do You Think We Are?: The Seen and Unseen in Family History

by Yoshinori Kasai

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The desire to discover one’s roots may be universal, at least during a certain period in recent history, though I’m not sure whether it stems from modern people’s sense of rootlessness. In the 1970s, the TV drama Roots, based on the novel of the same name by Alex Haley, became a worldwide phenomenon. The novel was written as a result of Haley’s attempt to trace his own ancestry, who had been brought from Africa to the United States as slaves. At the time, it faced academic criticism that his work was not factual but merely fictional. In response, he used an interesting term, “faction,” meaning fiction based on fact.

Nowadays, the BBC TV programme Who Do You Think You Are? has been running for more than twenty years. Each one-hour episode follows a celebrity as they trace their own roots, visiting related places and using online resources, assisted by professionals such as local historians and curators. Claire Lynch writes in her paper on the programme, “The crucial distinction between this approach and traditional family history is the realignment of the central protagonist — it’s not called ‘who do you think they were’, after all,” and “What was once a process of giving life to the image of dead ancestors has been reversed; it is they who are now obliged to give meaning to the living” (Lynch 2011: 114–115).

There are also TV programmes in Japan that can be described, following Lynch, as “biogravision.” The most widely recognised one is The Family History, produced by Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK). In contrast to the BBC’s version, where the celebrity travels on their own, the Japanese programme features the celebrity watching a summarised video together with the television hosts. As for sources, the NHK version relies mainly on family registration records, while other materials such as archival documents are almost the same in both versions. However, the National Diet Library Digital Collections, which has recently introduced a full-text search function, is useful, especially for seeking specific documents such as directories.

I would like to introduce how people in Japan approach family history, as this may not be widely known outside Japan. In some families, genealogical charts or narratives written by ancestors still remain. However, if someone wishes to trace their own family history from scratch, the main resource, apart from interviews with relatives, is undoubtedly the official family register (koseki).

Japan’s modern family registration system began with the so-called Jinshin Register (Jinshin koseki), which was established in 1872 (the fifth year of Meiji) under the law enacted the previous year. It has since undergone five major revisions in accordance with changes in legislation and continues to the present. Until a few years ago, obtaining a copy of one’s koseki required visiting or mailing a request to the local government office of one’s honseki chi (permanent domicile). Nowadays, however, with an Individual Number Card (My Number Card), it can be obtained from any municipal office in Japan.

In the Jinshin Register (1872), each household entry included a status designation (zokushō), such as shizoku (former samurai class) or heimin (commoners). Viewing the Jinshin Register is now prohibited, and in other versions that once contained such information, the status designations have been blacked out and are no longer readable.

In Japan, there has been discrimination based on social status or place of birth, especially in the contexts of marriage and employment, and unfortunately it cannot be said to be entirely a thing of the past. To prevent such discrimination, access to the Jinshin Register and to any records containing status designations is currently restricted to authorised persons only. Many Buddhist temples keep a record of deaths among their parishioners, known as kakochō (registers of the deceased). For the same reason, a considerable number of Buddhist sects have completely prohibited public access to these records in recent years.

Under the Civil Code of the Empire of Japan, the family system was patriarchal, and each family register consisted of a head of household (koshu), who held specific rights as the head, and other members such as parents who had transferred the headship, as well as siblings, children without headship, and their spouses. After World War II, the family system was reformed, and today each family register is organised around a married couple and their children.

Under the old Civil Code, the headship included the right to consent to the marriage of family members. There still seems to be a residue of the headship system and an extended-family mentality, especially regarding marriage. For example, many Japanese people say “enter the family register,” when what they actually mean is “make a new entry in the family register.” Beyond the context of registration, expressions such as “You (the daughter-in-law) entered our family, so you should…” are also still heard.

Using family registers, it is possible to trace one’s ancestry back about one and a half centuries, although there are some difficulties in using them. For earlier periods, we may look for family trees, archival documents, or engraved inscriptions, as in other countries.

I have also traced my own roots and family history. By using family registers, I was able to identify up to seven generations, totalling around seventy direct ancestors. I then collected documents from local libraries and public archives and visited some of the places where my ancestors had lived. Through this process, I exchanged letters with previously unknown relatives and even found another relative who was also researching our family history.

Many of my ancestors lived in Hokkaido, a large island in the northern part of Japan that served as a frontier for Japanese settlers during the Meiji era (from 1868 onward). Under the Meiji Restoration, the former samurai class was dissolved, and many of them moved to Hokkaido to cultivate the land under severe conditions, as they had lost their stipends and occupations. It was an interesting experience for me to realise the connection between such historical events, which we usually learn about from textbooks, and my own family history. At the same time, however, I also felt the risk of being tempted to construct a story from only a small amount of information.

Some may arrive at a cosmopolitan way of thinking, seeing their search for roots as a process of connecting with a wider society or even with the world beyond their own family history (for example, see Momondo’s The DNA Journey).

However, we also need to be aware of the risk of becoming trapped in the narrow space between what we can know and what we can imagine. It is clear that intimacy, meaning the close relationships that shape our lives, does not consist of ancestry or kinship alone. Yet it is extremely difficult to approach the lived reality of intimacy as it was experienced by our ancestors in the past. When we try to get a little closer to that reality, all we can do, in the end, is to draw on as many different sources as possible.

In addition, we should remember those who face difficulties in accessing information about their roots. For example, the right of adopted children to know their biological parents varies from country to country. It is also not difficult to imagine how challenging it can be to trace one’s roots across national borders, especially today when international marriage and migration are not uncommon.

When we tackle the question “Who do you think you are?”, it is important to remember that we can only answer “We think,” not “We know.” In other words, the search for one’s roots always involves an unseen dimension, and it may even create something that remains unseen.

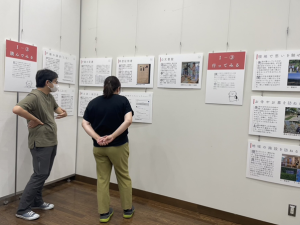

Image caption: Students looking at posters, as part of an exhibition titled Let’s Seek Family History.

My students and I at Keio University held a one-week exhibition titled Let’s Seek Family History at the gallery of the Kanazawa Ward Office in Yokohama City. The exhibition featured panels explaining how to collect documents and presenting several examples of family histories. We stayed at the venue every day, talking with visitors to learn, even a little, about their interests in tracing their roots.

We would like to know, if you are also interested in tracing your own roots, what motivates you and how you plan to approach it – please email me at kasa@keio.jp.

Reference

Lynch, Claire, “‘Who Do You Think You Are?’: Intimate Pasts Made Public”, Biography, 34 (1), 108-118.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Yoshinori Kasai, PhD, FRHistS, FRGS is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Keio University, Japan, and currently a Visiting Scholar at the University of Edinburgh.

FURTHER READING

Kasai, Yoshinori, “Findings Roots and Routes: A Case Study of the Namikawa Familly”, Hogaku Kenkyu: Journal of Law, Politics, and Sociology, 93 (11), 41-72. (笠井賢紀「歴史実践としての来歴探し―岩国藩士/岩見沢開拓民並河家を辿って」『法学研究』93(11), 41-72)

ABOUT THE CRFR BLOG

This is the official blog of the Centre for Research on Families and Relationships.

To keep up to date on all the latest posts and related events from CRFR, please subscribe via the button below.

This Blog is moderated by a CRFR representative who reserves the right to exercise editorial control over posted content.

Please note: the views expressed in a post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of CRFR.